2011-04-25

Barrett: come on you painter!

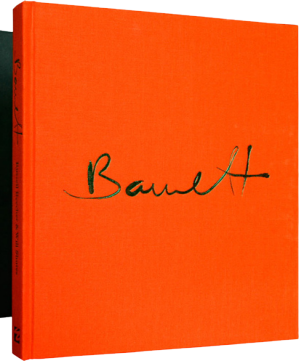

Barrett,

the definitive visual companion to the life of Syd Barrett, by Russell

Beecher & Will Shutes arrived at Atagong Mansion on the

second day of its release, Friday the 18th of March, but I have to

admit, I didn't really look at it, apart from some glancing through its

pages.

The reason is simple, the book is a visual biography collecting

many (unseen) photographs of Syd Barrett and his band The Pink Floyd,

facsimiles from letters to Libby Gausden and Jenny Spires and the very

first detailed catalogue of Syd's paintings, and I am more a man of

words, too many words some people say (and perhaps there is a a yet

undiscovered trail of prudence in me, as I am a bit reluctant to read

Syd's letters written to Libby and Jenny).

I care for Syd the musician but I don't get overexcited when a new

Barrett (or vintage Pink Floyd) picture appears on the web. First: this

has been happening on a regular basis since Barrett's death when people

suddenly remember that they have got an exclusive picture lying on their

attic. Second: these pictures will arrive, in due time, on the more than

excellent Have You Got It Yet? v2.0 Vol 11 Photo/Info DVD-Rom from Marc

Jones that can be freely downloaded at several places on the web, but I

prefer Yeeshkul

as it is the 'official' home for Floydian audio & video collectors.

Although not entirely legal this picture DVD was asked for by the Pink

Floyd management who gave Marc Jones a copy of Oh

By The Way, the Pink Floyd 14 CD compilation, in return. I am quite

convinced that the pictures of the Barrett visual companion will, one

day, mysteriously appear on a new release.

Photographs (editor: Russell Beecher)

Barrett is roughly divided into three unequal parts. Part one #1 shows

many unseen and previously unpublished pictures of vintage Pink Floyd,

#2 has pictures from the Syd Barrett solo era, about 110 pages in total.

They are printed in big format (one photo per page or double page, many

pictures have been spliced), in high quality and 'digitally' restored.

Most of the pages have a description of the picture, the date it was

taken and an appropriate quote or anecdote from the Cambridge mafia

or the photographer in question.

A so-called signature or limited edition has got a third, separate,

photo series by Irene Winsby, but to acquire these additional 72

pages you have to cough up an extra 235 £ (282 €). Unfortunately for me

the signature issue is bound in leather and as a strict vegetarian it is

against my conscience to skin a cow to watch a Barrett picture. If you

find this silly just try to imagine what the master of Sant

Mat would have said to Syd Barrett about that.

(A short description of the picture section can be consulted at: Rockadolly.)

Letters (editor: Russell Beecher)

Part two, the shortest one with 25 pages, is destined to letters from

Syd to Libby Gausden, Jenny Spires and ends with the famous little

twig poem to Viv Brans. Tim Willis already described some of these

letters in his Madcap biography, but didn't actually put these in

print (with one exception and about 4 times smaller in size).

Anoraks know that Syd decorated his letters with funny doodles and this

section is obviously more interested in the drawings than in the actual

letters. Libby and Jenny give cute explanations in what probably was a

very weird menage-à-trois (our quatre or quarante,

if we may believe the rumours about Syd's omnivorous female appetite).

Art (editor: Will Shutes)

Section three (over 90 pages) is what everybody has been waiting for,

for all these years. At least that is why I have bought the book for.

For ages fans have been drooling over Syd, the painter, but I never

really bothered. I did not put Syd Barrett in the same category as Ron

Wood and Grace

Slick who also smear paint on canvas (and that's about all that can

be said about them), but I adhered the theory that was written down by Annie

Marie Roulin in The Case of Roger Keith 'Syd' Barrett (Fish

Out Of Water, 1966).

The symmetries among the geometrical shapes painted by Barrett show an

embarrassing absence of 'concept', of hidden flaming which makes

doubtful the real artistic value of these works. As to the technique

they can compete only with works by low talented students of low

secondary school.

In other words, paintings of Barrett may have been slightly therapeutic

(and this can be debated: art sessions can also have the uncanny feature

of sliding an mentally unstable person further into regression) but - if

one can fully grasp Anne Marie Roulin's Italo-English - they

could certainly not be considered as art with a capital A. A daring

theory and certainly not liked by many Barrett fans, nor by his family,

and that is why journalist Luca Ferrari invented a female alter ego to

publish this controversial thesis (Luca's confession in Italian,

and an English translation on Late

Night.)

In the past biographies have tried to convince the reader that Barrett

was an art-painter pur sang, but none of these could win

me over, basically because writing about paintings without seeing the

actual work (or only two or three foggy examples) is like talking about

music without listening to it. For the first time in history a book

publishes Syd's whole oeuvre or what is left of it, about 100 of

his paintings; and Will Shutes has written an impressive 25 pages long

essay about Barrett's canvas outings throughout the years. While reading

the excellent essay one is obliged to constantly switch from text to

illustration and luckily the book has two ribbon-markers to facilitate

this multi-tasking.

Shutes admits that Barrett's work lacks 'consistency', a remark

originally made by Duggie Fields and cited in Rob Chapman's A Very

Irregular Head, but he immediately turns this into a plus factor.

Will concludes:

"The variety this implies is at the core of his originality."

, but one could use exactly the same reasoning to deduce that Barrett's

artwork isn't original at all.

Just like Julian Palacios

in Dark Globe has tracked down musical influences in Syd

Barrett's discography, Shutes cites several examples for Barrett's

graphical work. If there is one work of Barrett that stands out (in my

opinion, FA) it is the 1964-ish Untitled 15 (Cat. 20) lino print

with its evaporating crosses, but Barry Miles (also in A Very Irregular

Head) explains it has been clearly influenced by Nicolas

Staël, although Shutes reveals that there must have been some

secret Paul

Klee ingredient at work as well.

Rosemary Breen told Luca Ferrari that Barrett made up till ten paintings

a day, and even if this was exaggerated the one hundred in the Barrett

book only represent a small percentage of his output. Although nobody

actually witnessed Barrett destroying his work, it is assumed he burned

them or threw them in the rubbish bin. Some have said that Barrett

destroyed only those paintings that weren't perfect to him, but actually

he destroyed them all although some seem to have survived for a couple

of months before disappearing. The few exceptions are those he gave away

to family or visiting friends. Beecher & Shutes could trace 49 surviving

artworks by Syd Barrett and were lucky that Rosemary found some photo

albums of Syd's art. For most of his life Roger Barrett had the weird

habit of photographing his work before destroying it, as if he wanted

the destruction to be a bit less final. Opinions differ as well why

Barrett did this, and range from a mental disorder to an artistic

concept. Will Shutes:

Like Rauschenberg's

erasure

of a drawing by de

Kooning in 1953, Barrett's act of destruction is not a negation – it

achieves something new. Barrett is doing something when he destroys what

he has done, not merely erasing it.

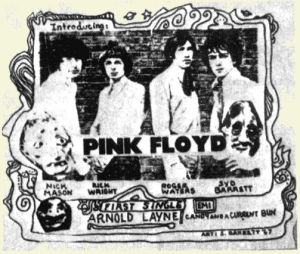

Even a Barrett scholar can have it wrong sometimes, the author describes

an Arnold Layne flyer, allegedly dating from March 1967, as designed by

Syd Barrett, unaware of the fact that it is fan-art, dating from the

late seventies, early eighties, and published in a Barrett fanzine. A

quick glance on Mark Jones' HYGIY picture DVD would have settled that

once and for all (remarked by Mark Jones at Late Night: Barrett

Book).

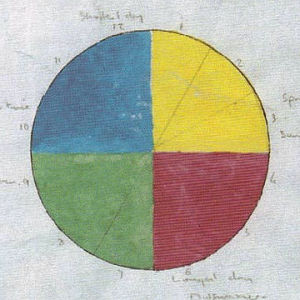

What intrigues me is that Roger Barrett continued to make abstract and

realistic paintings, as if he was afraid to make an irrevocable choice.

Personally I find his water-coloured landscapes or florals

uninteresting, although they do show some métier, especially

compared with the abstract works of the seventies or eighties that are

visually more compelling but technically mediocre. I'm quite fond of Untitled

67 (2005) that represents a pie chart of the summer and winter

solstices, although some

will of course recognise it as a pastiche of the Wish

You Were Here cover

art. That's the main deviation of the maniacal Pink Floyd and Syd

Barrett fan, seeing links that (perhaps) aren't really there.

This book contains the best descriptions and illustrations of Syd's

artwork, it is a collector's dream, but in the end Will Shutes can not

convince me that Barrett was a graphical artist in the true sense

of the word. It's a matter of personal opinion and I'm not sure if

Barrett knew it himself or if he even cared.

I hope the authors will not hold it against me if I tell that this book

is not destined for the average Floyd or Barrett fan. It contains no

juicy stories of feeding Syd biscuits through a closed locker door. Its

sole purpose is to ease the hunger of the Barrett community that is

easily recognised by its general daftness and its big pockets.

Despite the blurb that states the opposite Barrett is not essential for

the music loving fan, but the book is no waste of time for those that

want to acquire it either. Barrett has been made with love, caring and

respect for its subject, is a work of art and quality and has been

authorised by the Estate of Roger Keith 'Syd' Barrett. But at 90 £ (108

€) for the classic edition (including delivery) it is also pretty

expensive, perhaps not overpriced, but still a lot of money.

In his witty introduction Russell Beecher writes that over the years

there was "a need for a well-researched, intelligent, and

well-thought-through account of Syd's life and work". I completely

agree. He then continues by stating that this was fulfilled with the

publication of "Rob Chapman's excellent An Irregular Head in 2010".

Thank you, Russell Beecher, but I prefer to make up my own mind. In my

humble opinion Chapman's biography fails against at least one of the

qualities you have mentioned above. Those in need for an independent

opinion can consult Christopher Hughes's Irregular Head review at Brain

Damage, by and large the best Pink Floyd fan-site in the world.

Russell Beecher proceeds:

An Irregular Head is the definitive textual work on Syd.

What you now

hold is the definitive visual work on Syd's artistic life.

The two

books compliment one another.

Did I just pay 90 £ for a vaguely concealed commercial, wished for by

the Barrett Estate? The Barrett book is quite exceptional and possibly

'the definitive visual work on Syd's artistic life' indeed, but linking

its destiny to An Irregular Head, way off definitive if I am

still allowed to express my opinion, undermines its own qualities. This

feels like reserving a table at Noma

in Copenhagen to hear René

Redzepi announce that the food will reach the level of the local

McDonald's. Can I have some ketchup on my white truffles, please?

Some will find me overreacting again, but I had to get this off my

chest. Although a bit superfluous, and destined for the capitalist über-Syd-geek

alone, Barrett is far too luxurious and well-researched to have its

image tramped down.

The Church wishes to thank: Dan5482, Mark Jones, PoC (Party of Clowns)

and the beautiful people at Late Night.

Mark Jones posted a 13 minutes video review of opening the book for the

very first time (after having disinfected his hands first). It is more

than worthwhile watching: First

look at 'Barrett', the book, by Russell Beecher & Will Shutes.

Sources (other than internet links mentioned above):

Beecher,

Russell & Shutes, Will: Barrett, Essential Works Ltd, London,

2011, p. 10, 11, 145, 162, 163, 170, 175.

Chapman, Rob: A Very

Irregular Head, Faber and Faber, London, 2010, p. 49, 232.

Ferrari,

Luca & Roulin, Annie Marie: A Fish Out Of Water, Stampa

Alternativai, Rome, 1996, p. 31, 95, 97.

No comments:

Post a Comment