http://joshalanfriedman.blogspot.com/2010/04/jack-ruby-dallas-original-jr.html

INTERNET HOME OF MUSICIAN AND WRITER JOSH ALAN FRIEDMAN

[WYATT DOYLE, MODERATOR]MONDAY, APRIL 12, 2010

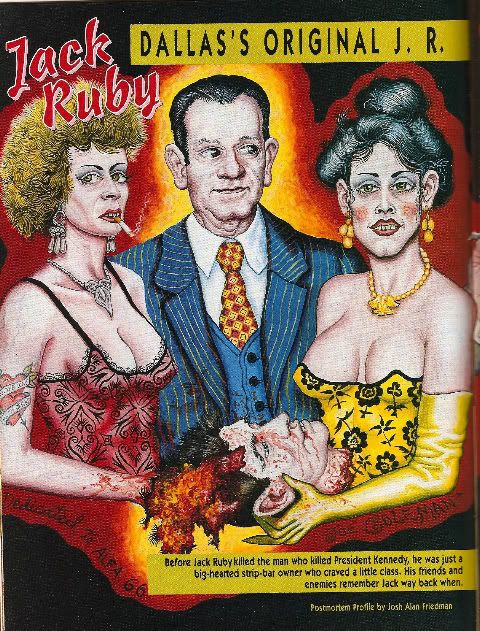

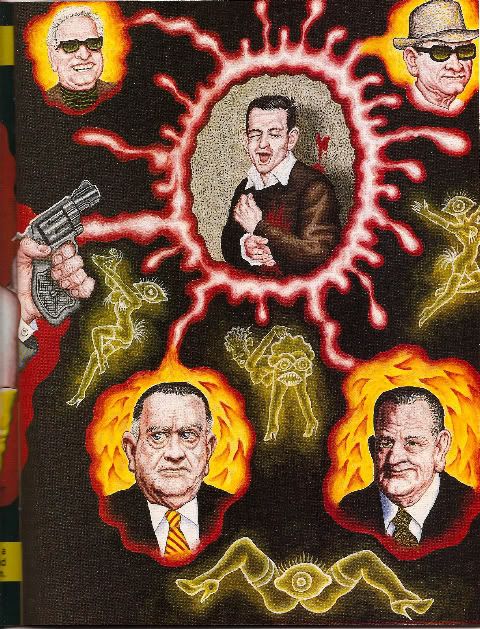

Jack Ruby: Dallas’ Original J.R.

artwork by Joe Coleman

artwork by Joe Coleman

Dallas Homeboy Was Standup Club Owner to R&B Musicians

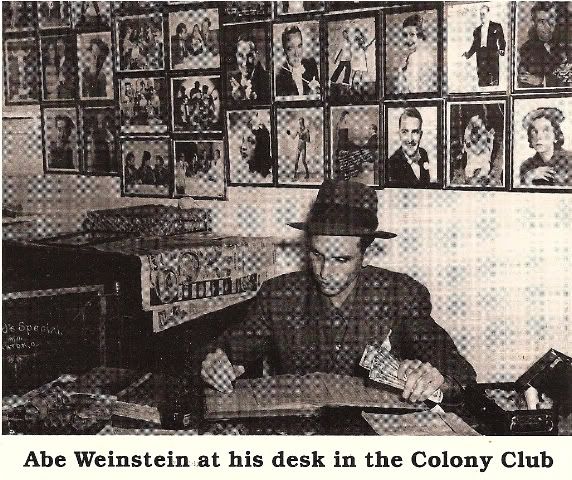

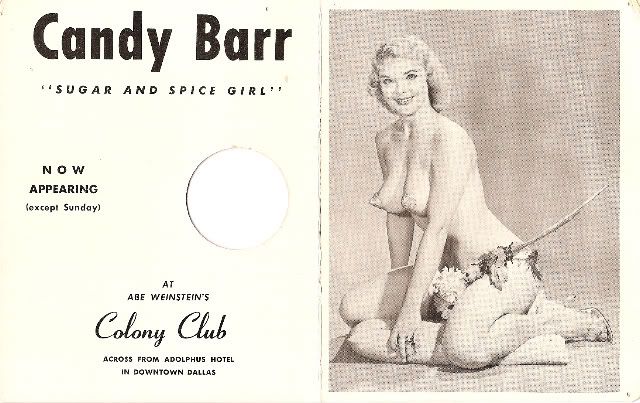

Jack Ruby would have turned 80 on March 25, 1991. I tried to gather a round table of former Ruby strippers for this occasion. After much detective legwork, I could not turn up one aging broad—all of Ruby's girls had vanished into the smoke of assassination lore. What follows instead are reminiscences of friends, foes, musicians and acquaintances who were still at large. He is frozen in our consciousness as the charging, black-suited patriot who gunned down Oswald on national TV two days after Kennedy’s death. Ruby believed he avenged his president's murder, saved Dallas’ reputation in the eyes of the world, made the Jews look good and spared fair Jacqueline the horror of a murder trial.Jack Ruby has figured in countless conspiracy theories, works of fiction and history books. He remains a star player in the American mythology of the JFK Assassination. A librarian at the Dallas Public Library refers tiredly to the huge assassination file log as “the Kennedy junk.” In 1990, Ruby’s executor-attorney was asking $130,000 for the .38 Colt Cobra that killed Oswald, along with some mundane possessions, like an undershirt Jack bought at Sears. (Who the hell would desire Jack Ruby’s undershirt?)An international glare came upon Jack Ruby’s dark little corner of Dallas night life on November 25, 1963. His second-rate strip joint, the Carousel, became the world’s most famous burlesque. Yet few customers ventured in after Ruby hit the front pages.“Anybody coulda killed Oswald, the way people’s feelings was running at that time—it didn't surprise me it was Jack,” says Dallas Deputy Sheriff Lynn Burk, who knew Ruby well, and was present when Oswald was captured at the Texas Theater. “I’m surprised some policeman didn’t kill Oswald first.”“He stuck by what he did,” says Captain Ray Abner, who was Ruby’s personal jail guard. “He said he loved Kennedy and that he was glad he did it. But I believe Jack just intended to wound Oswald. Spend a couple years in prison, sell a book and movie rights. He was a small figure who came up from the Chicago underworld. He was a guy who wanted to be a big-shot.”On Ruby’s last day as a free citizen that November morning in ’63, he was a paunchy, balding, 52-year-old burly-Q operator. He had oily, slicked-back black hair, a cleft in his chin, five-o’clock jowl shadow, and he wore cuff links, a tie stickpin and diamond pinkie rings.The Carousel was located on Commerce Street, one flight up, between a parking garage and a short-order restaurant. Strippers’ 8x10s hung over the entrance. A $2 cover allowed horny patrons entrance to a square, barn-like room with dark-red carpeting and booths of black plastic. Jack Ruby’s stage was the size of a boxing ring, with a five-piece bump-and-grind orchestra, but no dancing. The bar was boomerang-shaped, finished in gold-plated plastic and gaudy gold-mesh drapes. The black barkeep, Andy Armstrong, was Ruby’s right-hand man. Overhead hung a gold-framed painting of a stallion, which Ruby believed had “real class.”Obsessed with “class,” he operated from a dingy little office in the back with a gray metal desk and small safe.Terre’ Tale, a Dallas strip queen of the ’60s, had a dozen routines. The crowd favorite was an Uncle Sam act in which her boobs marched in time with a hup-two-three-four soundtrack. She met Ruby when innocently answering a Carousel newspaper ad for a cocktail waitress: “The black bartender told me to come back with the sexiest outfit I had. When I came back, they sat me down next to a guy with more arms than an octopus. I didn’t even know the Carousel had strippers. I’d never seen a strip. The girls laughed at my reaction. ‘When Jack sees you, he’ll have you on amateur night this Friday.’ But Jack Ruby was nice to me. ‘Does your body look as good as your face?’ he said. ‘No, I have two kids,’ I told him. Then he told me he could make me a star, put me in an apartment, send me to the beauty parlor every day.”Terre’ Tale refused Ruby’s offer, but a few years later she was headlining the Colony Club, two doors down from Ruby at 1322 Commerce. Abe Weinstein’s Colony club was Dallas’s most reputable burlesque from 1939 to 1973. Ruby envied this deco cabaret, which seemed to possess the elusive class he so craved.“My club was a nightclub,” says retired owner Abe Weinstein, now 83. “His was just a joint. I had big names; he had nobody. When he came from Chicago to Dallas in ’47, he came up to my club right away. He was told there’s a Jew runs a club, that’s how I met him.”Ruby, whose God-given name was Rubenstein, ran a few music spots before opening the Carousel right next to Abe in 1960. Ruby was a tremendous pain in the ass, bottom-feeding off the Colony’s action for three years. “My relationship with Jack was bad,” says Weinstein. “He threatened to kill me one week before he killed Oswald. I’d had him barred from the club. He tried to hire away my waitresses and employees. Here’s my opinion: Jack Ruby killed Oswald because he wanted to be world-famous. If he’d have killed Oswald before the police got Oswald, he would have been a hero. But it was no great thing to get him in the police station.” Ruby was particularly jealous of amateur night at the Colony and the lines it drew. There was no such thing a jail bait—girls in their mid-teens could hop onstage and strip.“I started when I was 15,” recalls former stripper Bubbles Cash in her North Dallas jewelry-pawn shop, Top Cash. “If you were married in Texas, you could do anything your husband said you could do. I married at 13. I told my husband I wanted to be a dancer and take Candy Barr’s place as a star in downtown Dallas. The ladies were like movie stars, glamorous, classy. The first time I took my clothes off onstage was great. I wore a red, white and blue dress, and when I unzipped, everyone went crazy, and my husband was proud. It was amateur night.”Eventually Ruby ripped off the amateur-night idea, sweet-talking local secretaries who’d never gotten naked before an audience onto the Carousel stage.Bubbles recoils at the mention of Ruby, whom she never worked for: “I was told by Abe don’t even go near his place. The Carousel had a bad connotation; the girls weren’t on their best behavior. They did some hookin’ outta there.”Weinstein, who lives alone with his memories, has almost no contact today with any of the strippers who graced his establishment. “I hadthe biggest stripper, Candy Barr,” boasts Weinstein. She was another figure associated in myth with Ruby. Abe pronounces her name with the same emphasis one would use for a Milky Way candy bar. “I named her, started her in the business, managed her. She packed the house every night.”

Ruby was particularly jealous of amateur night at the Colony and the lines it drew. There was no such thing a jail bait—girls in their mid-teens could hop onstage and strip.“I started when I was 15,” recalls former stripper Bubbles Cash in her North Dallas jewelry-pawn shop, Top Cash. “If you were married in Texas, you could do anything your husband said you could do. I married at 13. I told my husband I wanted to be a dancer and take Candy Barr’s place as a star in downtown Dallas. The ladies were like movie stars, glamorous, classy. The first time I took my clothes off onstage was great. I wore a red, white and blue dress, and when I unzipped, everyone went crazy, and my husband was proud. It was amateur night.”Eventually Ruby ripped off the amateur-night idea, sweet-talking local secretaries who’d never gotten naked before an audience onto the Carousel stage.Bubbles recoils at the mention of Ruby, whom she never worked for: “I was told by Abe don’t even go near his place. The Carousel had a bad connotation; the girls weren’t on their best behavior. They did some hookin’ outta there.”Weinstein, who lives alone with his memories, has almost no contact today with any of the strippers who graced his establishment. “I hadthe biggest stripper, Candy Barr,” boasts Weinstein. She was another figure associated in myth with Ruby. Abe pronounces her name with the same emphasis one would use for a Milky Way candy bar. “I named her, started her in the business, managed her. She packed the house every night.”

Abe claims Barr never worked for Ruby or had anything to do with him. But according to sax player Joe Johnson, Candy Barr came after hours to Ruby’s Vegas Club, in the late ’50s, to strip. “All the girls came over to the Vegas to strip,” says Johnson, who led a five-piece R&B group there. Johnson worked for Ruby six years, starting in 1957. His trademark was belting out sax solos as he walked along the bar top. “I was part of a family. Ruby was the best boss I had in Dallas. After he shot Oswald, the FBI followed me everywhere I’d play. I got six pages in the Warren Report.”Legendary Dallas-born Big Texas Tenor, David “Fathead” Newman, took hometown gigs at Ruby’s Vegas and Silver Spur dives, when on leave from Ray Charles.“The thing I remember most about Jack Ruby,” chuckles Newman, “were the stag parties in his clubs. Whenever the striptease dancers came out, he’d want the musicians to turn our backs, ’cause these were white ladies. He’d say, ‘Now, you guys turn your backs so you can't see this.’ But the strippers would insist that the drummer watch them so he could catch their bumps and grinds. So, Jack says, ‘Well, the drummer can look, but the rest of you guys, you turn your backs on the bandstand.’”Ruby’s penchant for barroom brawls kept him in minor scrapes with Texas law. Deputy Sheriff Lynn Burk, a dapper 67, remembers the frontier days of Naughty Dallas. He was a frequent lunch mate of Ruby’s, and still has Jack’s Riverside phone number in his phone book. Burk ironed out some of Ruby’s barroom troubles.He first entered Ruby’s music joint, the Silver Spur, in 1953: “Jack was stayin’ open late; there was suspicion he was serving liquor after hours.” Working undercover, Burk visited the club with a pint of whiskey and poured himself a shot, in the wee hours. Ruby politely told him to take it outside, thus abiding by the law. Burk was impressed.Pre-Kennedy Assassination Dallas had small-town camaraderie, whereby the Texas Liquor Control Board supervisor could meet for lunch with a burlesque owner. Ruby often brought sandwiches by the dozen up to police headquarters. Free drinks went to servicemen, even reporters, who Ruby ingratiated himself with. That’s why he wasn’t seen as out of place in the basement where Oswald was transferred.

Burk says he enjoyed Jack’s stories about a fighting childhood on the East Side of Chicago. Ruby had been a Chicago ticket scalper, then sold tip sheets at a California racetrack. He came to Big D after the army discharged him in ’47 with a good-conduct medal and sharpshooters rating.Burk recalls that Ruby was a good fighter who lifted weights and sparred with former lightweight champ, Barney Ross, who appeared as a character witness in Ruby’s murder trial.“When I was assistant supervisor of the Liquor Board in Dallas, a man called one day, wanted to know what we did to proprietors who beat up customers. I said you come to my office, and if we prove a breach of the peace, we can suspend his license.“So this great, big man, well dressed, comes in, some executive with LTV. Said he was down at the Carousel, he’d gotten separated from some friends. He thought they might have entered the Carousel; so he went up and paid admission, walked around, didn’t see ’em; so he asked for his money back before leaving. They said no, wouldn't give him his money back. He said, “Well, I’m not staying.’ They said, ‘Well, we’re not giving your money back.’ Then he said the proprietor knocked him down. He got up, and the proprietor knocked him down again.“I said, ‘I’ll get Jack Ruby down here; you identify him.’ I called Jack. I said, ‘Come on down, and come to my office first, you understand?’ Because the complainant and the supervisor were sitting in the other office.“I said, ‘Jack, there’s a man in the next room you beat up at the Carousel.’ He remembered. I said, ‘We’re goin’ in there, and you be the most humble damn man ever walked into that damn office.’ So we go in, and I say, ‘Mr. Smith, this is Jack Ruby.’ Jack said, ‘The first thing I wanna do is apologize.’ The man said, ‘Why did you knock me down the second time?’ Jack said, ‘You’re a lot bigger than I am,’ and described a fight where he knocked a man down once who got up and bit his finger off. Ruby showed his missing finger. He said that was the reason he always hits a man a second time. He said, ‘You can bring your whole office to my club; I'll feed them and give them drinks—I’m just sorry for what happened.’ The man dropped the complaint.”Abe Weinstein tells this anecdote about Ruby’s temperament: “There was a famous Dallas society doctor that lived in Highland Park. He was a good customer of mine, never bothered anybody or fooled with the girls. For years, every time his wife left town, he’d come up to the Colony. Then a month passed, two months, I never saw him. I called a meeting with the girls, but nobody seen him.“One day I’m walking by the Adolphus Hotel on Commerce, and I ran into Dr. Ross. He told me there’d been a doctors’ convention in town. A colleague from Los Angeles stayed with him, and Dr. Ross showed him the city. Took him up to Ruby’s place first, and he didn’t like the show. Dr. Ross walked down the steps and said he’d take the guy next door for a real show. Jack Ruby happened to be standing behind and heard the remark. When they got to the bottom of the steps, Ruby grabbed Ross by the neck and knocked out all his teeth. He couldn’t report it to the police because he was a Highland Park society doctor—what was he doin’ in this joint?“But that’s Jack Ruby, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. If you went into his club, he’d never seen you before, and said, ‘Jack I’m hungry; I don’t have a place to sleep,’ he would feed you and give you a place to sleep. But if he didn’t like you, he’d stab you in the back.”Virtually all the strippers who worked for Jack Ruby have evaporated from the city of Dallas. Just try searching for a Double Delite in the phone directory. “I didn’t live 47 years by talking about it,” spat one ex-husband of a Ruby stripper, who hung up.“You’re talking three generations of strippers back,” explains Shane Bondurant, a 1960s burlesque star who now preaches at the Rock of Ages church. Ms. Bondurant once twirled a ten-gallon Stetson hat from one boob to the next, whilst spinning two pistols at the hips. She used 24 live snakes in her act, and made headlines when one of the two lions she kept in her trailer park bit her leg.Like Bubbles Cash, Terre’ Tale and Abe Weinstein, Ms. Bondurant knows the whereabouts of not one single Ruby girl: “I would figure most became prostitutes, addicts or died. A stripper’s career is ten years, and the few who survive afterward must be quite strong and pull their lives together.”Ruby’s girls were not that strong. There were suicides that became part of the conspiracy lore. Baby LeGrand, whom Ruby wired money minutes before killing Oswald, was found hung by her toreador pants in an Oklahoma City holding cell in 1965. Arrested on prostitution charges, her death was ruled a suicide.Tuesday Nite was another suicide. And in August 1990, worldwide interest was stirred by the latest conspiracy theory: The son of a Dallas cop claimed his father shot JFK, and presented a plausible scenario of evidence. His mother had worked at the Carousel, overhearing Ruby and her husband discussing the planned assassination. She was then given shock treatments, and is now allegedly too ill to speak to reporters.Certain Ruby girls showed great devotion for their boss. Little Lynn liked Ruby enough to show up at the jail crying after Ruby was imprisoned. The 19-year-old, blue-eyed stripper carried a Beretta pistol in her scarf to give him. She was arrested at the entrance.Shari Angel, once billed as “Dallas’ own Gypsy,” also kept a candle burning for Jack Ruby. In a 1986 Dallas Times Herald interview, the former Carousel headliner tried to raise money for “a medal or monument for Jack. He was a wonderful man.” Angel described him as a mother hen to the girls, who took them to dinner and bowling. She married the Carousel emcee, Wally Weston, who later died of lung cancer. After years in an alcoholic haze, she found Jesus and pulled herself together. “You know,” she told the Herald, “I’ve seen [Ruby] hit a man—I mean a real hard shot—and then pick him up and feed him for a week. He was big-hearted. If I could just get a monument to him, then maybe we could finally lay him to rest.”Angel once again relates Ruby’s attack-repent ritual of belting some guy out, only to turn around and “feed” him. Needless to say, the city of Dallas never erected a monument. A little-known literary gem,Jack Ruby’s Girls, was published in 1970 by Genesis Press in Atlanta. “In Loving Memory of Jack Ruby,” read the dedication by Diana Hunter and Alice Anderson. “Our raging boss, our faithful friend, the kindest hearted sonuvabitch we ever knew.” This reflected the love-hate relationship of a half-dozen strippers profiled within.There was Tawny Angel, who Ruby fell “insanely in love with,” tripping over his speech. Until her, say the authors, Jack Ruby-style sex encompassed only superficial one-nighters with “bus-station girls, trollops and promiscuous dancers.”“Jack Ruby’s Carousel Club was in the heart of a city that never took the Carousel to its heart,” wrote the authors. “Dumping” champagne was a Carousel ritual. Girls accidentally spilled bottles of the rotgut stuff, marked up to $17.50 from a $1.60 wholesale price. Jack Ruby beer went for 60¢ a glass, and it was shit. He encouraged the bar girls not to drink it, just to waste it when sitting with suckers in the booths. Ruby didn’t allow hooking, claimed the authors, just the false promise of sex so they could hustle champagne.Jack chiseled money from customers, yet loaned money to friends. He beat, pistol-whipped and blackjacked unruly patrons down the stairs. Spend money or get out—that was the attitude of the man who avenged President Kennedy’s death.“I never believed there was a conspiracy between Jack and anyone,” states Deputy Sheriff Burk, never before interviewed about Ruby. “Because Jack Ruby had two dogs he thought more of than anybody. If he had any idea he was gonna kill Oswald, he woulda arranged for those dogs. It was a spontaneous outburst—he was over at the Western Union when they moved Oswald. It was timing.”Not many folks came to visit Ruby in jail, according to Ray Abner. Immediately following the arrest, Abner was assigned to guard Ruby’s jail cell for over a year. He kept an ear on phone calls, listened to the arguments between Ruby and his sister Eva, watched him shower, heard him break mighty wind, even must have smelled it.Ruby’s cell was isolated from the rest of the prisoners, near the chief’s office, with full-time security. “Jack liked special attention,” says Abner. “He felt like they oughta prepare meals the way he wanted ’em. I ate strictly jail food, same as the prisoners, and I insisted he do the same. None of the girls came to see him. Just his lawyers, his sister Eva and his brother Earl. I couldn’t help but overhear his conversations; so I’m pretty sure he wasn’t involved in any conspiracy.”Ruby was riding high in the months after he shot Oswald. He doted over his daily shipment of fan mail, over 50 letters a day congratulating him, calling him a hero. “But after a while,” Abner remembers, “the fan mail dropped off, and he got depressed.”Ruby was convicted, and he died of cancer in January 1967 while he was awaiting a retrial. In the meantime, those who made their living in his champagne-hustle world had to go elsewhere for work. Jack Ruby’s Girls documents the pilgrimage of two strippers after the Carousel closed: Lacy and Sue Ann applied for jobs at Madame De Luce’s upscale whorehouse in the Turtle Creek area of Dallas. But Madame believed Ruby “ruined” women as potential prostitutes. All tease, promise, but no fuck is what Ruby taught them. The reputation as a Ruby Girl was a stigma for those who tried to become hookers.Jack Ruby didn’t allow that type of hanky panky in the Carousel. “This is a fuckin’ high-class place!” he would remind any doubting Tom, Dick or Harry, as he kicked them down the stairs.

© 1991, 2010 Josh Alan Friedman

The Dallas Public Library has a nice copy of "Jack Ruby's Girls" signed by several of Jack Ruby's girls. https://catalog.dallaslibrary.org/polaris/search/title.aspx?ctx=1.1033.0.0.6&pos=8&cn=64280

ReplyDelete