http://www.furious.com/perfect/moldydogs.html

(via kopper)

But that's a parallel universe. Here, in this universe, the one in which Buddy Holly got on that damned plane and the government went and killed poor Sam Cooke, Roxon, Major, and Wheeler have real jobs, and The Moldy Dogs are relegated to that vast purgatory of bands that, for whatever reason, never made it. More than just some obscure band waiting for their turn at being reissued and consequently forgotten again, The Moldies are one of the great rock and roll stories- a band that helped to bring the new revolution of punk rock to the city of St Louis, and cleverly bridged the gap between sixties pop and punk rock like few other bands could. And so what if their story ends in what can only be described as failure. Even the most successful rock bands fail more than they succeed, and some of the greatest failures in rock music have influenced some of its greatest successes. Failure is (and always has been) more attuned to the true spirit of rock and roll than success and for every great success story rock and roll has produced, there's a million other stories of failure that are infinitely more interesting than any success story. In many ways, the best thing one can say about The Moldy Dogs is that their story is one of those stories- a story not so much about how the band failed, but how rock and roll has failed. Like the greatest rock and roll bands, the story of The Moldy Dogs can be told several different ways. In many ways, they were the quintessential rock and roll band. Social misfits who were at once ahead of their time and stuck in the music of the past, they were inspired by the same things that have inspired every important rock and roll band since Jerry Lee Lewis set fire to a piano. "We were young men," says Paul Wheeler, who played bass for the band in 1976 when they were kings of the emerging St Louis underground. "We liked fun. We liked women. We liked music." In other ways they were trailblazers that paved the way for punk rock in the American Midwest (in which the battles of punk rock were really fought, and eventually won). Today, they are one of those bands, like Rocket From the Tombs or The Micronotz, to which a great debt is owed that is never really repaid- a band that, at the time, everyone knew would be important, but whose importance is understood today by only a few. "The Moldy Dogs are always brought up as a starting point of things in St Louis," says Jason Rerun, host of Scene of the Crime, an underground music show on St Louis' independent radio station KDHX 88.1. "[They] were definitely there right before and during the first days of the late '70's punk explosion." "They predated any sort of organized St Louis punk scene by a good year or two," says Brad Reno, a St Louis resident and frequent contributor to TrouserPress.com. "They were so far under the radar that no word of them would've gotten much further than the people at their gigs," he continues. "I never really heard about them until the early-mid '80's, when the punk and new wave folks would be at shows all trying to prove how early on they'd gotten into punk. The cool kids could talk about having seen Max Load, BeVision, the Heels or the Oozekicks, but the really cool ones would trump everyone by saying 'I saw the Moldy Dogs!'" And in other ways, they were one of the oddest miscalculations rock and roll ever produced. "Our songs came from left field with weird subject matter and were littered with lyrics that we hoped would be intriguing enough to capture the listener's interest," says Wolf Roxon, who co-founded the band in 1972. "There was usually something out of the ordinary going on, not just a romantic or emotional problem over a lover. Likewise, we were under produced and raw by contemporary standards. You may not have liked us, but you would have to admit that no body on the radio sounded or wrote like us." Paul Major was a loner from Louisville, KY who spent his teenage years messing around with the guitar and had come to Webster looking to start a band. "I became passionate about music as soon as I heard fuzz psych guitars as a kid," says Major. "They took me beyond my head and I felt connected. I had heard some Top 40 Beatles and Stones songs but when guitars went Hendrix, I knew I had to be part of that and the cultural shift they represented to me changed my life. I had to get a guitar, I had to, and ever since, it's been central in my life in many ways." Roxon's insights are a little more revealing. "Paul did come to college armed with a few originals he wrote for his senior high school project the year before," says Roxon. "One, entitled 'The Moldy Dogs' obviously became our namesake. He had a couple others that were equally strange and provocative, so much that, after he performed these tunes at his high school assembly, the school principal apologized to the students for having to sit and listen to the songs!" The pair met through mutual friends on campus and the band actually formed from the good graces of a member of the farer sex. "My girlfriend had split up with me and I had tickets to see Neil Young. So I just asked Paul if he wanted to go," Roxon says. "Incidentally, Neil Young kinda sucked but Linda Ronstadt, the warm up act, literally blew him off the stage. She really rocked back then. After the show, we returned to the dorms, borrowed a couple guitars and jammed all night. We actually recorded it and Paul still has the tape somewhere. I heard it a few years ago and while our playing is not entirely impressive, it does demonstrate that we were able to "read" each other from the very start. We could improv amazingly well considering it was our first time playing together." The duo began jamming and collaborating in dorm rooms, experimenting with the classic sounds of '60's pop, and delving into the murky underground of The Velvet Underground and The Stooges. "Our major influences were any mid-1960s British band," Roxon says. But especially The Kinks, The Yardbirds, and The Rolling Stones. We also loved The Velvet Underground, The Doors, Bowie, and The Stooges. To a lesser extent, we played Dylan, surf rock, and various off-the-wall Top Ten hits, often tongue in cheek, from one-hit wonders. Basically, if we liked a song for whatever reason, we played it. We never played a song we hated unless we were trying to destroy it, which was easy for us." "We played very loudly, through my Fender Concert Amp," he continues. "Most of our rehearsing took place in the dorms and once we burst into a song you could literally predict within ten seconds how long it would take to hear a knock on the door from some dazed dorm student, begging us to stop playing. We tried various locations on campus--the stairways, weight room, basement bathrooms, but nothing muffled our sound from the sensitive student's ears." Using only electric equipment, the band was limited, both temporally, by the complaints of their neighbors, and creatively by, well, the complaints of their neighbors. At the time, they were just two guys blaring fuzz at each other, a true garage band without the solace of a garage. They nomaded around campus, occasionally trying out guest musicians while fumbling to find their own sound, until one day when Roxon wandered into McMurray Music and picked up an Epiphone acoustic. "I was amazed at the rhythmic bite I was able to get out an acoustic," he says. "The natural harmonics and overtones seemed to 'fill the holes' in my strumming and added those percussive thumps that only an acoustic instrument can provide. I also realized the benefit of not having to lug my electric gear over to Paul's dorm room. Since I had graduated from Webster College, I had an apartment about ten miles away. So that Epi became mine." This acquisition proved to be a watershed moment in the development of The Moldy Dogs sound. "Our sound was immediately transformed," says Roxon. "My rhythm playing sounded tighter which opened up some new sonic space for Paul to wail. We were no longer competing. Our guitars complemented each other and, sort of by accident, gave us a signature sound. Strong acoustic, percussive rhythm became our solid base while Paul's electric not only provided distorted and edgy leads, but also cut through on fills and bass lines. We didn't change our playing style all that much, but you could now distinguish what we were attempting to do. And once we could hear each other, we became better listeners, then better arrangers. Shortly after the arrival of the Epiphone, we were having our Sunday session in Paul's dorm room. And, as usual, about ten minutes into the rehearsal, there was the proverbial knock on the door. I sighed, opened the door, and yelled , 'OK, we'll quit.' Outside, in the hallway, stood a very confused underclassman. 'No, no', he stammered. 'We don't want you to quit. We were wondering if you could turn up a bit--we can barely hear you down in the Quad.' When he sensed my confusion, he added, 'Look out your window. There's a bunch of people really diggin' you guys. Could you come outside and play?'" The new arrangement didn't just give the duo a few fans, it also gave them a shot of self confidence. "The most important effect of switching to acoustic and recruiting a few listeners was that Paul and I realized we can play live as a duo and no longer needed to depend on other members," says Roxon. "And, in turn, by playing out regularly, we came into contact with others on our wavelength. Not only did we learn four or five hours of sets, but we also began writing and arranging more. Within a year I was writing 6-10 songs a month and Paul was churning out about the same number, but of higher quality." As the pair worked to hone their skills, and role players continued to drift in and out of the band, they began to attract a bit of a following among local weirdos and social outcasts. "Truthfully, only the gay students thought we were cool because we played The Velvet Underground, The Kinks, the New York Dolls, and Bowie," says Roxon. "There were a couple of occasions when a lone student council member went out on a limb and pushed for us to play at a major dance. We would recruit some new members and rehearse intensely, but the powers that be would inevitably get us scratched from the show." "We really banged our heads against the wall by trying to get gigs at clubs and bars," Roxon continues. "We were usually rejected before we auditioned due to the fact that we didn't look 'country' enough or hippy enough. We were once thrown out of a folk club because Paul played an electric guitar." But what a band considers frustration, fans and writers call persistence and that persistent frustration eventually paid off. And though dividends may have been miniscule in terms of fans, they were influential. "Wolf and I were cranking out lots of crazy songs and playing our first shows, a key one being a run at a place called the Pastrami Joint where a following developed," says Major. "We met other locals who were into what we were. The buzz was 'There's this duo with acoustic and fuzz guitar who do Stooges and Velvet Underground songs - somebody else in St Louis is into those bands besides us!' and a little scene started." One of the people that migrated into the scene forming around the band was Paul Wheeler, who played bass in a cover band called The Dizeazoes. "I heard about this duo that played some of the music I was into including David Bowie and The Stooges, along with lots of old '60's classics and a friend and I went to see them" says Wheeler. "During the performance Wolf would ask rock and roll trivia questions between some of the songs," he continues. "My friend and I always seemed to be the ones who knew the answers." Wheeler, who was disgruntled with the direction The Dizeazoes were headed, took a chance and asked Roxon and Major if they were looking for a bass player and was a full-fledged member within a week. "Wolf and Paul were nice guys," Wheeler continues. "They were the best musicians I had played with up to that point and probably some of the best I ever played with. Even better, the material they wrote was really something special. It was exciting to be in a band that was creating new music, and I thought what we were doing was some of the best stuff I was hearing at the time. Punk rock was just starting to explode then, and I thought we had something that might really take us somewhere." "The chance of success was unlikely, especially in St Louis," admits Wheeler. "But it was damn good fun to make a lot of noise and be involved in something that previously you had only dreamed of doing. St Louis was a pretty boring place to grow up in the '70's. Being in a band, even if it only amounted to making noise in the basement, held a promise for the future." That promise turned into what would be described today as a scene but at the time was just like minded friends hanging out. It wasn't that bands began to pop up around The Moldy Dogs, but bands that already existed began to gravitate together, hanging out, jamming, hooking up, and sharing ideas and members. "I remember once in the summer of 1976, my family went on a summer vacation and I chose to stay behind," says Wheeler. "Paul Major, Wolf, and I hung out in the house rehearsing or playing records and one night we took an acoustic guitar on out on the front porch. Paul and Wolf passed it back and forth and we just improvised stupid songs - the stupider the better. It was good fun, and impressive that we seemed comfortable enough with each other to be bouncing silly ideas off each other and just chatting and drinking beer. No, they weren't very good songs, but they were good fun and very silly." "For fun on a Friday night we'd all go over to KWUR, the Washington University radio station where there was a weekly punk program," Wheeler adds. The show was DJ'd by David Thomas who would later be a part of the influential Chicago band DA! "It became quite a group of us, and most were in one band or another," Wheeler continues. "We'd just hang out there, listening to the music played on the program and socializing. It was the place to be if you were into the St Louis punk scene." "He featured an entire show of punk rock," says Roxon. "Among the many imports fresh from the U.K, he also featured our demo tapes. It was a hip place to hang out and talk shop," recalls Roxon. "Everyone was fresh and excited," says Major. "I was playing in a band for the first time, what I knew I had to do ever since I first heard fuzz guitars on my little transistor radio. Playing in a band with people who were into the same stuff I was, realizing something special and original was happening. I could be creative, have fun, and feel a sense of purpose." In true rock and roll fashion, things began to happen quickly and the friendships the band would form eventually morphed into The Punk Out Show, the first organized showcase of punk rock in St Louis. Held in the "party room" of an apartment complex in June of 1976, the event was organized by the Toler Brothers, owners of Akashic Records, a local record store that catered to the emerging punk scene. The show included bands like The Back Alley Boys, an early incarnation of The Cigarette Butts that was fronted by Norman Schoenfeld who was as important to the development of punk rock in St Louis as The Moldy Dogs. It's also memorable, at least to music geeks, for the performance of Bruce Cole, the other half of The Screaming Mee Mee's, who performed a solo set. During his performance, Jon Ashline, the other half of the Screaming Mee Mees was tending bar. According to legend, Ashline sang along for a song or two from behind the bar, which is the closest the infamously agoraphobic Mee Mees ever came to performing live. But, as is typical with all developing scenes, there were complications. Paul Wheeler's recent departure from his previous band, The Dizeazoes, who had been booked to headline the show before The Moldy Dogs, was still smarting, and the remaining members of The Dizeazoes tried to get The Moldies booted from the show. "The Dizeazoes were pissed at Paul for leaving the group right before a major show and, in their minds, stealing their gig, so they went to Toler and got us booted off the bill," says Roxon. "Norman Schoenfeld went to the Tolers and told them 'If the Moldy Dogs don't play, then we don't play'," Roxon continues. "That would have cancelled the entire show, since some members of The Cigarette Butts were also backing Mike Shelton, lead singer of The Dizeazoes, who was doing a solo act thing with The 'Butts and others. So Toler gave in and we got back on the bill. Norm did us a big favor. The night went incredibly well musically. Everybody gave a stellar performance." The show was a bit chaotic. "About all I remember of that show is that our drummer, who had played with The Dizeazoes for a very short period at one point, had happened to run into me, and, as we needed a drummer, we got him to play drums for us at that show," says Wheeler. "He was drumming so damn hard the bass drum was moving forward with each beat," Wheeler continues. "He had to chase after it, and play, and move his drum stool along as he did. I probably didn't notice it at first, and apparently no one else did either. Once I did notice, I made a point of putting my foot in front of the bass drum to keep it from sliding forward. So, I had to spend a good deal of the show there with my foot holding back the bass drum, which was a shame, 'cause I like to move about when I play, but I guess it gave me something to accomplish besides just playing the bass lines." There was also drama outside of the stage. "Our drummer that night got the shit beat out of him in the bathroom," says Roxon. "A friend and I drove him to the hospital, against his wishes," recalls Wheeler. "He really needed it and I never heard from him again after that." "People thought Ashline did it but that's highly doubtful," says Roxon. Ashline had previously been considered as a potential drummer for The Moldy Dogs but was rejected for whatever reason. "Ashline was really pissed at Wheeler because he knew I wanted him in the Moldy Dogs and he blamed Wheeler for being the one who blackballed him," says Roxon. "So a drunk Ashline walked up to Wheeler, grabbed the cigarette out of his mouth, threw it on the floor and stepped on it. Wheeler picked up the cigarette, examined it, nodded, and looked at Jon and said, 'Got a light?' Ashline pulled out his lighter and, after that, they got along." The scene was beginning to establish itself - there were places for bands to play, people to attend the shows, a friendly radio program, even drama between bands and a great mystery for historians to discuss (to this day, no one knows who attacked the drummer). "It was a lot of fun," says Paul Major. "In those days, I couldn't wait to get a guitar in my hands, so I loved the rehearsals and jams. It was at a time when I was leaving college and supposedly walking into a job world and I did music instead so it was liberating." Soon after came The First St Louis Punk Fest, a small gathering of local bands that took place January 11, 1977 at a club called Fourth and Pine, which was meant as a farewell to the scene that the group had helped create. "Wolf was very secretive about a few things for this show," says Wheeler. "I was out enjoying the rest of the show when I finally saw Wolf's costume. I could see why he wasn't out in the club socializing. He had chosen to wear cut-off blue jeans and red tights. I remember shaking my head, leaving the dressing room and returning to the main room." "Our set was good with very few flubs," says Wheeler. "We rocked it and really took things up a few notches. Lyla, who was our guest singer that night for three songs, got a good reception from the crowd and Wolf threw out posters at the end of the set which the crowd grabbed for. Were they disappointed or happy to find out they were Olivia Newton John posters?" By that time, The Moldy Dogs had decided that they could make it in the music business. Roxon had decided to quit his job teaching school, he and Major moved in together, and the band decided to move to Los Angeles, figuring that the small successes of St Louis would translate into larger success on the West coast. "A little early scene was developing in L.A. and the weather was a plus," says Paul Major. "Around 1975, The Moldy Dogs began to consider themselves more than just some recreational players filling their lives with music," says Roxon. "There was very little doubt in my mind that we would become household names and achieve the ultimate fame reserved for the very few. We were totally committed and literally everything we did was focused on this highly elusive goal." "During the month of December 1976, we rehearsed new band members for upcoming recording sessions, continually rearranged songs slated for recordings and recorded practice demo tapes, recorded four song in a real recording studio, worked day jobs (I was a teacher, Paul worked in a nut factory), wrote and arranged nine new songs, rehearsed The Moldy Dogs for the upcoming First Punk Rock Fest, rehearsed with a solo, guest performer performing at the First Punk Fest, prepared adverts, posters and publicity for the Punk Fest, called our friends to attend, dodged and purposely played phone tag with a gay record executive who claimed his major label was looking for a punk band and we could be it (provided I...), hung around with our new girlfriends, went to court with my landlord for raising our rent, moved out of my apartment, liquidating all of my furniture, assests, and car, to pay for the L.A. trip, prepared for our upcoming trip to L.A. by making contacts, had and attended various Christmas/New Years parties, played out as a duo and attended other friends' gigs, constantly studied Django Reinhart, The Dictators, The Stones, and Bowie on the turntable in an attempt to steal every guitar lick, cooked, cleaned, packed, drank, drove, ironed, doctored, changed guitar strings, attended film classes, and the list goes on..." Roxon sums this all up with only a few sentences. "We seemed to be surviving by giving every minute its sixty second run, gathering no moss, with things falling into place due to our naive energy. And that was fun. Why else would anyone live like this?" "It was like we injected ourselves with a rare disease, the desire to create the next wave of rock and roll music, and hoped to find a cure, success, in time." "The songs were often tricky to learn, but fun to play once you had them down," says Wheeler, who did not accompany the band to L.A., opting instead to finish college at the University of Missouri. "Many of the songs were gentle with a dark sweetness, or a somewhat clever slant," he continues. "I really hadn't heard anything like some of these songs before. There was a definite '60's pop influence, but it was twisted into new shapes, which reflected the punk attitude. The songs could be appreciated, both intelligently or simply for the sweetness of the pop hooks." More than anything, it is the "sweetness of the pop hooks" that differentiates The Moldy Dogs from other bands at the time. Though they did write some kick ass barn burners that would have rivaled anything emerging from New York or London in terms of sheer punk energy ("Sat Chit Ananda", "Bongo Man"), they also produced songs like "Bring Me Jayne's Head" and "Baby Bones in the Basement", which were arty and dramatic. There were also folk elements thrown into the mix, and at times the band can sound like a strange amalgamation of David Bowie, Fairport Convention and Genesis. Indeed, listening to the their demo tapes leaves the listener with the impression that The Moldies were good enough that they could have mastered of any type of rock and roll they decided to follow. Part of the problem in figuring the band out may have been the fact that Roxon and Major were perhaps too eclectic, too interested in putting their own stamp on everything happening in rock and roll in the mid-1970s and claiming each genre as their own. Their most memorable songs, however, strike one chord in particular. "Had they made bigger waves at the time, they'd probably be categorized as part of a Mississippi River states corridor Power Pop movement," says writer Brad Reno. "St. Louis is almost exactly halfway between Memphis, where Big Star was based, and the Chicago region, where you couldn't throw a rock in the mid-70s without hitting a band like Cheap Trick, The Shoes, Pezband or Off Broadway." But, in the early days, punk rock was played 1,000 different ways in 1,000 different places throughout the world and it wasn't until much later that punk rock was played one way in a million different places throughout the world and the sound of punk rock would become immediately recognizable. Strongly influenced as children by the polite rebellion of the British invasion, and as teenagers by the impossible blurt of The Stooges and The MC5, Roxon and Major undoubtedly struggled to reconcile their influences with their expression. Punk rock, in the classic sense, was only just beginning, and The Moldy Dogs considered themselves to be in on the ground floor, actively participating in the creation of the idea and sound of punk. As a result, it was impossible for the band to be strongly influenced by the canon of classic punk rock because, at the time, there simply was no codified definition of what a punk rock band could be. The Ramones formed in 1974, two years after Roxon and Major began jamming together, and the Sex Pistols didn't hit The States until well after that, by which point The Moldies had already decided that they were destined for greatness under the punk banner, not because they were playing punk music, but playing music in the spirit of punk rock. "We never wanted to sound like anyone else, even when the punk movement exploded in 1977," says Roxon. "We loved it primarily because these punk/New Wave outfits were influenced by the same groups as us, but we never wanted to emulate their sound. We had already been there." The simple truth is that The Moldy Dogs never sounded like a punk rock band, and today wouldn't be considered one even if they had released an LP or a single. It may have been in their blood but it wasn't in their heart. They were songwriters, craftsman who had more in common with Lennon and McCartney than Rotten and Vicious, and their songs came about through careful consideration and countless hours of rehearsal rather than the great momentum of the social rebellion taking place around them. Their music wasn't political like The Clash, wasn't nihilistic like The Sex Pistols, nor was it part of a larger artistic scheme like that of Richard Hell or Patti Smith. The brilliance of The Moldy Dogs was that, while their songs possessed as much energy and nihilism as any other punk band out there, they insisted on holding their songs in check with a strong backbone of '60s pop, and they didn't see a great deal of difference between "I wanna be your dog!" and "I wanna hold your hand!" In short, the band was creating a form of punk that wasn't a violent reaction to the course rock music had traveled, but a natural development from that course, part of the endless riffing on the basic idea of rock and roll that has fueled every innovative band from Buddy Holly, to The Pixies, to Nirvana, to Arcade Fire. "There was a demand for anything different from the prevailing commercial product," says Paul Major. "This opened the door for lots of people to make widely divergent styles of music, but it all got lumped into punk and then new wave. The same thing had happened in the sixties under the name psychedelic, and like then, everything seemed up for grabs. We did do punk styled aggressive stuff, but had also done unusual, experimental things that would be termed acid folk if an LP existed and collectors discovered it now." In addition, The Moldy Dogs played their particular brand of punk rock in St Louis, which, though it was a large city, was still locked in the heart of the Midwest. It's easy to forget, or simply ignore, that what was considered 'punk' in New York or London would have been considered very possibly illegal in the Midwest in the 1970's, and The Moldy Dogs, in many ways adapted to and worked within those confines. The music they created was both rebellious and, if not socially acceptable, at least not socially objectionable. It was this approach that allowed to the band to help create a punk scene in a city that really shouldn't have had one, and later attempt to create a career in music that shouldn't have been attempted, that no kid from the Midwest should have ever considered. The point was that people were excited about their music, which was the main attraction to punk rock in the first place - it was music that was exciting, exhilarating, interesting, and original. The band also had a different approach to their music than the majority of the classic punk rock bands who, more often than not, seemed to write music for the crowds of misfits and journalists that had gravitated to the scene rather than the masses. A story from Roxon an early gig is perfectly illuminates their approach. "At an early gig at The Grove, we played at lunchtime and opened our first set to a crowd of little old ladies with the tinted blue-gray hair and pant suits. We panicked and paged through all our set lists searching for something to play. We launched into The Kinks "Well Respected Man" then some Velvet Underground and some originals. They loved it and were unbelievably responsive to every song. It had to be our sound, because no little old lady back in the mid-1970's was going to get a kick out of hearing The Velvet's "Heroin," The Stones' "Parachute Women" or our own "Bring Me Jayne's Head." "The central premise of punk was to be crude, loud, and obnoxious," says Major. "The less technical skill the better. We were trying to be as skillful as possible in arranging our songs so they could appeal to a large variety of people." Wheeler believed very strongly in both the talent and vision of the band. "Paul Major and Wolf Roxon could play. They were well versed in all the folk chords, which previously I hadn't had much contact with. Their songs were intricate, and yet had some wonderful hooks. The lyrics were often vague enough to let you read your own stories into them, as well as containing dark images entwined in their recesses." When the band left St Louis, they left thinking that if they couldn't make it in St Louis, they could probably make it anywhere. Opting, perhaps mistakenly over New York in January 1977 for L.A., they seemed to be walking into a paradise compared to St Louis. "We left for L.A. around the time of a blizzard in January in St Louis," says Major. "L.A. and warm beaches seemed like a tastier move at the time. The punk bands were just forming, only a few shows were happening, but the beaches were great. We sang on the beach for change in February. It was so cheap there at the time, and that was a plus. But it turned into a surreal vacation." Though the weather was great and the opportunities may have seemed endless, L.A. proved to be a lot like St Louis. In L.A., the band made contacts, played the occasional show, tried their best to ingratiate themselves into the music business, and basically lived the same life they had in St Louis, "real jobs" and all. "In Hollywood, I worked at an all-night news stand," says Roxon. "You may think of L.A. as being balmy, but in February at 3:00AM on the street, it feels frigid, especially when you left your coat back in St. Louis. "Paul made low-cal desserts in a restaurant that catered to incredibly overweight ladies. He also worked in a glitter factory but alas, the glam scene was on its way out, so all that free glitter did nothing for us. We both worked in a bubble bath factory. They marketed bubble bath in plastic containers the shape of a squirrel and a poodle, the cap screwing on the top of the body. On the assembly line, the women would place the head of the squirrel or poodle on the cap and Paul or I would pound it down with a mallet. You had to hit that head just right to knock it in place. Those critters came fast, so bam! bam! bam! one after another, smacking those heads as fast as humanly possible.. We were the best headbeaters in the place and nobody started any shit with us. We worked many other awful jobs too, just to support ourselves since the group barely made enough to buy guitar picks." Despite such distractions, creatively, The Moldy Dogs were still riding high (collectively, between Roxon, Major, and Wheeler, Roxon estimates the band has a catalog of 1200-1500 songs), and the band was convinced that success was waiting just around the corner. Brimming with self confidence and an impudent determination to not compromise their vision, the band would make several decisions which in retrospect would be considered mistakes. During their stint in L.A., Roxon and Major were offered a job backing drummer Sandy Nelson at an oldies themed show in Las Vegas, which they rejected. "A friend turned me on to Sandy," says Roxon. "He called him on the phone, introduced me, and we had a pleasant conversation. When I asked about the nature of the musicians he was seeking, Sandy replied 'Look, do you know three chords?' I answered that, between Paul and I, we only know two, but 'give us a week and we'll figure out another.' He loved the answer though my friend was shocked. We were so sure that our big break was just around the corner that we decided not to be tied down to Vegas." But all of their impudence and self confidence couldn't hide the fact that the freedom in which the band had reveled inside the confines of St Louis didn't jive with the complicated world of major labels and marketing the band had wandered into. Major and Roxon found themselves lost in a veritable sea of rock and roll nightmares that defined the mid-1970's. Their sound was unique enough to be interesting, but somehow, not interesting enough to be unique. They needed work, they needed band members to stick around in order to form a cohesive unit, they needed studio time, they needed to make good decisions, they needed luck, and they needed a chance. "Making it in any aspect of the entertainment business in New York City or Los Angeles was like playing musical chairs with 100,000 people and just two chairs," says Roxon. "What were your chances of even getting close to a chair when the music stopped?" "I spent countless hours of literally every day taking our demo tapes to the big record labels, then, eventually the small ones," Roxon continues. "In the mid-1970's, the record companies would, for the most part, listen to your demos, or at least a song. We were rejected by all. They simply could not imagine a market for our music and they realized we were about as far as one could be from disco or even the over produced rock they promoted." "I visited one small label in 1977," Roxon continues. "It was a two person operation - the A&R person at the front desk screened the tapes and passed her top choices on to the president of the label. When I went back to the office a few days later, she greeted me warmly but had a hurt look on her face. She explained to me how excited she was after hearing the demo. She thought we were the most unique songwriters who ever crossed her desk, passed the recording on to the president with her highest recommendation. But he rejected the tape. The reason: we needed to work on our overall sound. We were competent musicians but we needed to discover a standout, defining sound that usually comes through finding the right members and devoting countless hours to playing and experimenting. In other words, we were simply too bland. "She went on to tell me the story about her friend from Florida who, for thirteen years had been recording demo tapes all winter then coming to L.A. in the summer to shop his tunes. Every year he faced rejection and every year he returned home and recorded or reworked another batch of song, then bounced back to L.A. for another round. She asked if I'd ever heard of him. His name was Tom Petty and he called his group The Heartbreakers. He just signed a contract this year and his first album was in the stores." It didn't take long for Major and Roxon to sour on the Sunset Strip and the duo decided to move their pop hooks and dark images back to St Louis for a brief stint before heading off to New York where Roxon and Major would enjoy more success but still face many of the same problems. "The music business is, by far, the most corrupt business on this planet," says Roxon. "Nothing else even comes close - banks, oil companies, or political parties. "Connie Francis once said: 'When I started in the 1950s, the music business was run by a group of people who knew a lot about music, but nothing about business. Now they know a lot about business, but nothing about music.' Believe me, in the late 1970s and early 1980's, the music execs knew nothing about music or the business. And they could have cared less. So dealing with them was a challenge which we tried to ignore and hoped it would go away or someone else would do it on our behalf. For The Moldies no one stepped forward. "You can do everything right in your rock group and still fail miserably," Roxon concludes. At some point during the transition from Los Angeles losers to New York near darlings, The Moldy Dogs effectively broke up. "At first, we picked up where we had left off in 1976," says Roxon. "But as the summer wore on, our disappointments mounted. The live gigs we had were scarce, and the contacts we had were not delivering. Paul Major and I were slowly coming to the realization that we were still very far from achieving our destination. I remember Paul lamenting that we may still need four to five years of development at the rate we were moving. He was right, and the fact is, we simply did not have that much time." Though it was a difficult, and still contentious, decision, Wheeler was kicked out of the band over creative differences before the band left for New York. "Paul Major and I had sacrificed a lot for The Moldy Dogs and hoped other members would do the same. But when arguments began to surface over what we considered minor requests for cooperation, well, let's just say the seeds were planted." Wheeler has a different version of the events which led to his departure. "Wolf principally booted me out of the band," says Wheeler. "I suspect that it was because I was under the illusion that it was a democratic band, and though I recognized that Wolf was the front man, and that if anyone was, he was certainly the leader of the band, I didn't feel that gave him the right to make all of the decisions, and regularly argued with him. That didn't sit well with Wolf." The Moldy Dogs left for New York in autumn of 1977 and, as in L.A., couldn't quite find their place. "Paul and I tried our best to find future members for The Moldies," says Roxon. "But when it became apparent it was going to take a while we decided to throw a group together with Peter Mathieson and a twelve year old drummer named Ralph Grasso." The new band was called The Tears, but it was all in the spirit of The Moldy Dogs. "We were shocked by how musically primitive the New York scene was in late 1977," says Roxon. "So we filled our sets with old Moldy Dogs songs, even some Wolfgang and the Noble oval and Screaming Mee Mee's tunes. Of course, this was not the group Paul Major and I had in mind to form when we split The Moldies in St Louis. We also played the Bleecker Street club/bar scene calling ourselves The Imposters." Eventually, The Tears would dissolve as well, and Roxon and Major would drift their separate ways, though neither strayed far from the other. Major formed The Sorcerors ("a rather heavyish metal band ala the future Guns and Roses," says Roxon), for whom Roxon filled in on bass for a short time. The duo regrouped in 1980 under the name Walkie Talkie and would enjoy a modest amount of success. Wheeler, who had moved to New York at the same time as Major and Roxon, had joined The Outpatients and would gig around New York with The Metroes, the band Roxon formed after The Tears. In 1998, Major and Roxon reformed The Moldy Dogs and experienced a small renaissance. "In the late 1990's, we reunited The Moldy Dogs in New York and once again played various clubs as well as recorded extensively. During this period we recorded more songs than all of our prior history together," says Roxon. "Unfortunately both Paul and I were approaching our late 40's and other commitments now took precedence. Those years of being young kids with no strings attached were long gone. So The Moldy Dogs were shelved once again. No doubt, we reached our highest musical achievements during this period, but we just ran out of time. Or maybe time ran out on us." The Moldy Dogs

Part 1 by Jack Partain

In a parallel universe, one that's actually cool, Wolf Roxon is a rock and roll god, Paul Major is a guitar legend who parties with Keith Richards in London on weekends, Paul Wheeler is one of the most sought after sidemen working today, and The Moldy Dogs, the band formed by Roxon and Major in St Louis in 1972, is preparing to embark on an already sold out, epic reunion tour of the world's biggest venues. It's their fourth reunion, but this one is not about the money, they swear, but about the fans. Their opening act is a reunited Talking Heads, who agreed to the gig not for the money or the fans, but for the chance to share the stage with their idols. They'll play Madison Square, Wembly, Red Rocks, Budokan, hell, even a headlining set at Coachella, but it all starts with a quiet, unannounced set at New York's CBGB's where a standing room only crowd of carefully chosen friends, acquaintances, and longtime fans gather for a warm up gig which consists of Roxon and Major jamming out on acoustic guitars, improvising riffs and solos, laughing, drinking beer, and telling stories about the old days when rock and roll wasn't created in dressing rooms and studios but in basements and garages. Friends like Paul Wheeler and Jeff Rosen are brought on stage to laugh and jam, tell stories of their own, and drink strange concoctions served by the quiet bartender named Jon who sometimes can be seen singing along behind the bar. Hell, they even thought about inviting the Human Wah-Wah on-stage, but he was drunk and pouting in a corner so 'fuck him anyway' they thought and played way too late, signed too many autographs, and stumbled to their limousines knowing they'd probably be too hungover in the morning to remember most of it but whatever. It's what legends do.

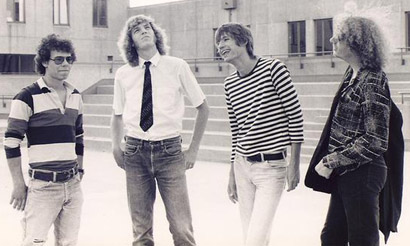

The Moldy Dogs were formed in the fall of 1972 when Roxon met Paul Major while attending Webster College in St Louis. Roxon was a St Louis native who had cut his teeth as one half of the basement freak out duo Wolfgang and the Noble Oval, the self described "First Punksters in St Louis." The band, which included Jon Ashline (who would become one half the notorious Screaming Mee Mees) didn't make it further than the stairway outside of Ashline's bedroom door (and then only to toss a drum set down the stairs as a drum solo), but it did reinforce Roxon with the drive to pursue music, and several of their songs he'd written would follow him into his work with The Moldy Dogs and later projects. The Moldy Dogs

Part 2 by Jack Partain

Roxon describes a typical month in the life of the band:

No comments:

Post a Comment