http://www.ponderosastomp.com/blog/2010/05/hep-me-the-senator-jones-story/

Hep’ Me – The Senator Jones Story

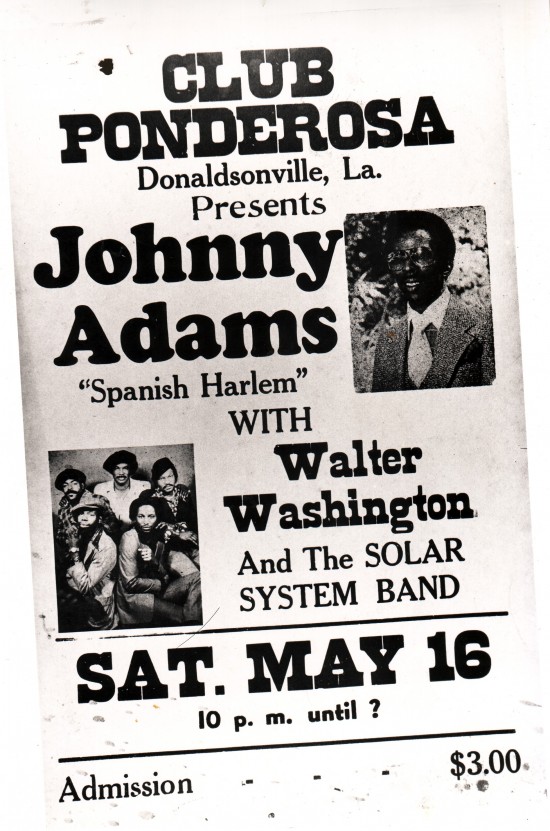

Since the late 1950s to the dawn of the new millennium, there have been well over 200 different independent labels operating in and around New Orleans — perhaps the most of any American city outside of Nashville and New York. In the early days the record business appealed to individuals of various backgrounds who shared an entrepreneurial streak. For an investment of just a few hundred dollars, you could record and press several hundred singles. With a little luck — and maybe a $20 bill or a fifth of whiskey given to the right jock or jukebox operator — you could recoup your investment or, better yet, score a bona-fide hit record. With the abundance of R&B talent in New Orleans, it would happen with mind-boggling frequency. As one old-school label owner and producer pointed out, “If you threw 10 (singles) out there and one stuck, it would pay for the other nine, and you still made money. That’s how the business worked.” With that kind of playing field, the independent record business obviously attracted many interesting and fascinating characters — and none more so than Senator Jones. Between the late 1960s and early 1980s, Jones recorded an enormous amount of local R&B talent and headed up several labels under the “Erica Productions,” umbrella, a business he ran out of a small, cluttered office in the Masonic building on St. Bernard Avenue. Johnny Adams, Charles Brimmer, Barbara George, Chris Kenner, Tommy Ridgley, Walter Washington and James Rivers were among the numerous New Orleans artists to record for “the Senator.” A street-smart hustler who knew the independent record business backwards and forwards, Jones discovered several artists, but perhaps more importantly, he also extended the careers of many veteran R&B performers. Senator Nolan Jones was born on Nov. 9, 1934, in Jackson, Miss., and his family moved to New Orleans in 1951. Fond of the bright lights, Senator worked as a laborer but was drafted into the Army two years later. Eventually stationed at Fort Benning, Georgia, Jones sang with a vocal group called the Desperados, whose ranks included Oscar Toney Jr. and Jo Jo White. The Desperados occasionally opened shows for the Five Royals as well as Hank Ballard and the Midnighters at nearby clubs. Jones was discharged in 1957 and returned to New Orleans, where he began sitting in at local clubs like the Dew Drop and Club Tijuana. Hooking up with Al Johnson, Jones helped write “You Done Me Wrong,” which Johnson recorded in 1958 for Ron Records. In the early 1960s, Jones began hanging out at Joe Assunto’s One Stop Record Shop on South Rampart Street along with the likes of Earl King, Johnny Adams, King Floyd, and Professor Longhair. Assunto was an important player in the local record business, as he was a retailer, a wholesaler, and a record-label owner. Befriending One Stop clerk Beryl “Whurley Burley” Eugene, Jones convinced Eugene that he might well profit from his connections with Assunto if he started his own record label. In 1963, the Whurley Burley label debuted with Jones’ truely dreadful “Call the Sheriff”/ “Let Yourself Go.” Senator Jones – Call the Sheriff The following year Jones cut “Sugar Dee” for Assunto’s Watch label and, later, “Einie, Meenie,Minee, Mo” for the International City label, which was owned by a local disc jockey, Bob Robbins. The latter single actually made some noise, and Jones got booked for some local sock hops. International City did another session on Jones that produced “Mini Skirt Dance,” which was leased to Bell. However, after four tries, Jones realized he wasn’t going to make it as a recording artist. However, bitten by the record bug, he decided to start working on the other side of the studio board. “I could see that local artists weren’t getting as recorded as much as they should,” Jones said in 1985. “I saw New Orleans acts steal the shows from national acts with hit records. That’s when I started thinking about producing.” In 1968, Jones founded his first label, Black Patch, named for the patch he wore for several years after losing his left eye in an accident, and recorded “The President of Soul,” guitarist and singer Rockie Charles from New Orleans’ West Bank. When Charles’ “Mr. Rickashay” failed to sell, he folded Black Patch and formed a new label, Shagg. Rockie Charles – The President of Soul “I recorded ‘Kid Stuff,’ by the Barons,” recalled Jones. “I put that record out on Shagg 711. Shagg was a nickname a lot of artists gave me. ‘Kid Stuff’ did pretty well. Cosimo Matassa leased it to Dover (distributors) during the session. He paid me $800, which paid off (arranger) Wardell Quezergue and the musicians.” Needing some startup capital to get off the ground, Jones got financing from club and motel owner Ferdinand Prout as well as two All South Records salesmen, Elmo Sonnier and Whitney Picou. The second Shagg single was by Guitar Raya cousin of Earl King, who had earlier recorded for Hot Line. Now highly collectable, the coupling of the intense “You Gonna Wreck My Life” and “I’m Never Gonna Break His Rules” was one of the best blues records to come out of New Orleans in the 1960s. After just two releases on Shagg, Jones decided to fold it and form several other labels, including Superdome, Erica, Jenmark, JB’s, and Hep’ Me. “As I got more and more artists, I didn’t want to go to the radio stations with seven records on the same label,” said Jones. “I knew the deejays would say, ‘I can’t play all these records; they’re all on the same label.’ So I started new labels and switched colors on the labels to make them look different.” Eventually, most of Jones releases would come out on Hep’ Me, a label that got its name in a curious fashion in the late 1960s. “When John McKeithen (from north Louisiana) was running for governor, he would get on TV and say, ‘Won’t you please hep me.’ Well, it got him elected. I figured if it was good enough for him, it was good enough for me too.” “That group was led by two brothers from Baton Rouge, Clyde and Brian Tolivar,” said Jones, “Bill Sinigal had recorded the original for White Cliffs, but the master was lost and they couldn’t press any more records. It was still a popular Carnival song even though nobody could buy it. Alvin Thomas plays tenor sax on my record because no one in the group could get that second-line sound.” That same year Jones also had a best-seller with Eddie Lang’s topical “Food Stamp Blues,” which was released on Superdome. A veteran blues guitarist from the north shore, Lang had earlier recorded for RPM and Ron. “Food Stamp Blues” eventually was leased by Jewel Records and became a modest Southern hit. Jones’ next taste of success was with deep-soul legend Charles Brimmer of New Orleans, whose smoldering “Afflicted” topped the local charts. The following year Jones produced Brimmer’s biggest hit, “The New God Bless Our Love.” Al Green had first recorded “God Bless Our Love,” but it was available only on an LP. Despite the pleas of jukebox operators and distributors, Green’s label, Hi, refused to issue the song on a single, hoping to extend the sales of the album. Jones was shrewd enough to realize there was a demand for a single of “God Bless Our Love” even it wasn’t by Al Green. Jones asked Brimmer to cover the song, and 48 hours after delivering dubs of “The New God Bless Our Love” to radio stations, Jones’ distributor, All South Records, had orders for 10,000 singles. Jones didn’t have enough money to press that many singles, so he leased “The New God Bless Our Love” to the Chelsea label in Los Angeles. Chelsea wound up selling 60,000 singles as well as 10,000 copies of a subsequent Charles Brimmer album produced by Jones. Charles Brimmer – Afflicted With his labels getting a tenuous foothold in the New Orleans R&B marketplace, Jones struck a deal with Marshall Sehorn. In return for access to the Sea-Saint recording studio owned by Sehorn and Allen Toussaint, Jones turned over a percentage of his profits to Sehorn and gave him the rights to license his material. Jones lost his best-selling artist in 1976 when he and Brimmer had a falling out and the singer moved to Los Angeles. However, the following year Brimmer’s place would be taken by “The Tan Canary” of New Orleans, vocalist Johnny Adams. Adams hadn’t recorded since 1975, when his longtime label, SSS of Nashville, went out of business. Adams hoped to get signed by a major or a national independent label, but after two non-promoted singles on Atlantic, he had no other offers. Jones had been after Adams to do some recording for him for some time, but as anyone who knew Adams knows, Johnny was never in a hurry to do anything. Finally, when gigs started to dry up, Adams realized he needed a new record on the jukeboxes to attract work. That’s when Adams and Jones came to an agreement. “Johnny was by far the greatest singer I ever heard,” said Jones. “The first time I booked the studio, he didn’t show up, which made me mad as hell (not a pleasant sight). I didn’t think he’d show up the second time, so when he did, we just pulled songs out of the air. That’s how the first single, “Stand By Me,” and the “Stand By Me” album came about. Marshall made a deal with Chelsea to release them.” While the “Stand By Me” album (which might have sported the most uninspiring cover of the decade) and his early JB’s singles were reworkings of soul classics, Adams’ later work with Jones was far more imaginative. Jones scored his first hit with Adams with an interpretation of Conway Twitty’s “After All the Good Is Gone.” Originally released on Hep’ Me in 1978, the single was a strong regional mover and caught the attention of Ariola. Ariola leased the single, coaxing it into the charts, and contracted Adams to do an album with Jones. The resulting LP, “After All the Good Is Gone,” is arguably the best one that Adams ever recorded. Johnny Adams -After all the Good Is Gone Adams continued to record great singles for Jones that sold well around New Orleans, including the telling country lament “Hell Yes I Cheated,” “Spanish Harlem,” “Please Come Home For Christmas,” “I Live My Whole Life At Night” and “Love Me Now.” The latter song was leased to PAID Records and briefly charted. By the early 1980s, Jones had begun issuing 12-inch albums. While he had the market covered in regards to singles, his album releases were mostly woeful. Canned graphics, blurry photographs, distain for dictionaries and proofreaders (Johnny Adams was referred to as “the tan canery” on the back cover of his initial Hep’ Me LP) and extremely short playing time were common on Jones’ LPs. Another consistent artist for Jones was Baton Rouge’s Bobby Powell, who joined Hep’ Me in 1978. Powell had a national hit with “C.C. Rider” in 1965 on the Baton Rouge label Whit after Jewel leased it. Powell recorded soul, blues, and gospel for Jones. “Bobby was a sweet artist,” said Jones. “He can deliver anything you ask him to. He does blues, but he also leads a choir at his church. We had a number of good records. I’m speaking of “Sweet Sixteen,” “The Glory of Love,” and “I’m a Fool For You.” Jones also recorded several New Orleans R&B veterans, including Chuck Carbo, Tommy Ridgley, Barbara George, Chris Kenner, and James Rivers. He also gave up-and-comers like the Las Vegas Connection, Walter Washington and Clem Easterling a chance to record. However, by 1985, many of the local stations Jones depended on for airplay were in the hands of out-of-state owners and corporations that devised their own national playlists. This meant that the chance to get a local single played on the radio in New Orleans were slim to none. When airplay dried up, it became impossible to sell his releases to record stores and distributors. Once that happened, Jones could no longer afford to record and manufacture records. “The stations in New Orleans forgot about us small record companies,” fumed Jones. “It got impossible to make a profit from a local record.” After Adams left to record for Rounder, Jones more or less threw in the towel and began managing a small motel on the West Bank. By 1990, he had moved back to Mississippi, where he divided his time raising goats, producing the occasional record (often on himself) and working as a disc jockey on a small AM station under the guise of “Mr. Bo Bo.” He briefly partnered with Ace/Avanti Records owner Johnny Vincent, but there wasn’t a room in Mississippi big enough to hold both their egos and they eventually split. Jones also did some talent scouting and occasional record promotion, most notably for Malaco. His best find might have been discovering “The Love Doctor” and steering him to Mardi Gras Records, and he also released an early CD by Sir Charles Jones on the Hep’ Me label. An era in the independent R&B record business ended when Senator Jones died in his sleep on Nov. 5, 2008, at his home in Bolton, Miss. Categories: Audio, New Orleans, R&B, Soul |

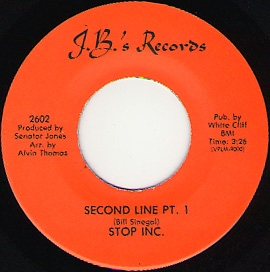

In 1973, local keyboardist, Ray J. (Raymond Jones) had the first release on Hep’ Me with a cover of Dr. John’s “Right Place Wrong Time,” which sold well around New Orleans. Ray J., who doubled as a prep school music teacher, also began arranging sessions for Jones. One of his first sessions produced the 1974 Carnival hit “Second Line Pt. 1 & 2″ by Stop Inc., which appeared on JB’s.

In 1973, local keyboardist, Ray J. (Raymond Jones) had the first release on Hep’ Me with a cover of Dr. John’s “Right Place Wrong Time,” which sold well around New Orleans. Ray J., who doubled as a prep school music teacher, also began arranging sessions for Jones. One of his first sessions produced the 1974 Carnival hit “Second Line Pt. 1 & 2″ by Stop Inc., which appeared on JB’s.

No comments:

Post a Comment